|

|

Logging with steam required a large work force regardless of the size of the operation. Until motorized vehicles and chain saws were used, it took more men to fall, yard and transport logs to mills than it did to cut the same amount of timber into lumber. Even a small camp might employ 40 or more men. A camp crew included timber fallers and buckers, saw filers and other maintenance personnel, men to operate the logging railroad, men to operate the donkey engine, and the cook and flunkies.

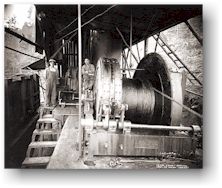

The falling crew consisted of fallers and buckers. Fallers cut down trees and buckers sawed the felled trees into lengths. Loggers used seven, eight, or nine-foot long saws, with a man on each end. These loggers faced great danger from trees falling or rolling on them. A rigger, or choker setter, then would put a choker around the log and attach it to the skidding or yarding equipment. The logs were then yarded or pulled from the woods to a landing or loading site. Usually this was done with the help of a donkey engine which was a steam, gasoline, or diesel engine with drums and cables that yarded, or pulled, the logs from the woods. Donkey engines began to be used in the woods in the late 1880s and came into general use in the next ten years. The logger who operated the donkey was called a donkey puncher. A logging technique called “high-lead” logging developed, requiring a steam-engine donkey, steel cables, and a single, tall, standing “spar” tree. While loggers set great store by the work done by the donkeys, the engines were a major cause of injury and death among loggers because of the tendency to set the woods on fire or blow up unexpectedly, or the propensity to break the rigging and send cables flailing through the air around them. In the 1930’s, gas/diesel-powered donkeys began to replace steam donkeys. By the 1950’s, steam had disappeared from the forests.

|

|

It was always dangerous to work under a spar tree, where the spotting line was pulling in empties, the tongs dangled form the loading jacks on the guylines overhead, the yarder was bringing in turns every few minutes, and always there was the chance of runaway cars going down the grade, plus the omnipresent risk of rolling logs crushing the unwary. Logging was then, and remains today, a business where a man literally had better know how to “run for his life.” [Source: Prouty, Andrew Mason. More Deadly Than War: Pacific Coast Logging, 1827-1981. New York; London: Garland Publishing, Inc. 1985.]

It was always dangerous to work under a spar tree, where the spotting line was pulling in empties, the tongs dangled form the loading jacks on the guylines overhead, the yarder was bringing in turns every few minutes, and always there was the chance of runaway cars going down the grade, plus the omnipresent risk of rolling logs crushing the unwary. Logging was then, and remains today, a business where a man literally had better know how to “run for his life.” [Source: Prouty, Andrew Mason. More Deadly Than War: Pacific Coast Logging, 1827-1981. New York; London: Garland Publishing, Inc. 1985.]

Shay Engines

The Shay geared locomotive was invented by Ephraim Shay, a Michigan lumberman, and patented in 1881. It was designed for logging railroads where the tracks are often temporary and always in bad condition, with sharp curves and steep grades. Their small wheels make Shays slow but since every wheel is driven, they are able to pull heavy loads for their size. Shay locomotives are either two-truck with eight wheels or three-truck with twelve wheels.

Heisler Locomotives

Compared to the Shay and Climax, the Heisler was a rather latecomer. In 1892 Charles L. Heisler received a patent on the locomotive that would also bear his name. Although superficially resembling a Climax, what set his locomotive apart was that the cylinders were slanted inwards at a 45 degree angle. The center shaft only drove one axle per truck, as the wheels in each truck were connected with a side rod. In 1894, the Stearns Manufacturing Company (Erie, PA) began reorganizations, and became the Heisler Locomotive Works in 1907. Just as with the Shay, there were two and three truck models, with sizes up to 90 tons. Heislers were made until 1941. There were 850 built, of which 32 still exist.

Climax Locomotives

Between 1875 and 1878, Charles D. Scott, a lumberman of considerable mechanical ingenuity, operated a logging tram road with a home made locomotive to handle logs to the Scott and Akin mill at Spartansburg, nine miles from Corry, Pennsylvania. Scott’s experiments with his home made locomotive lead to his invention of the Climax locomotive. The first Climax Locomotives built were very crude in appearance and bore little resemblance to conventional locomotives. A vertical boiler and two cylinder marine type engine was mounted on top of a platform frame, supported by a four wheel truck at each end. A round water tank was placed on one end and a fuel bin on the other. Power was transmitted to the axles by gears with a differential arrangement similar to the modern automobile, and driven by a line shaft connected to the engine through a two speed gear box. The frame, canopy type cab, and even the truck frames were made of wood. The first Climax locomotive weighed ten tons in working order, and was soon increased to fifteen tons. Production of Climax locomotives ceased in 1928.

|

|

Baldwin Locomotives

The Baldwin Locomotive Works was founded in 1831 by Matthias Baldwin. The original plant was on Broad street in Philadelphia, PA where the company did business for 71 years until it moved in 1912 to a new plant in Eddystone. Baldwin made its reputation building steam locomotives for the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, and many of the other railroads in North America and for overseas railroads in England, France, India, Haiti and Egypt. In the later days of the steam era, Baldwin was in the forefront of locomotive construction with the many 2-8-2 Mikados it built and its ability to build small quantities of unique designs, such as the Cab Forward 4-8-8-2s it built for the Southern Pacific. Also it was involved with its various railroad customers to develop new and improved locomotive designs, the last being the 4-8-4 Northerns. In the late 1940’s it was very clear that the steam locomotive days were over. Lima merged with engine builder Hamilton in an effort to get a foothold in the diesel market but made little progress. In desperation, Lima-Hamilton merged with Baldwin in 1950 to become the Baldwin-Lima-Hamilton Corporation. However, by 1956 BLH ceased production of common carrier size locomotives.

Whitcomb Locomotives

In 1878, George D. Whitcomb began manufacturing coal mining machinery in a small machine shop in Chicago, Illinois. In 1892, his growing business was incorporated as the George D. Whitcomb Company. Gasoline engines were a definite novelty in the closing years of the Nineteenth Century. However, Mr. Whitcomb concluded that a gasoline motor could be installed in small mining locomotives. In April 1906, the first successful gasoline-powered locomotive was built and eventually placed into service at a large Central Illinois coal mine. The Whitcomb manufacturing facility was moved to Rochelle, Illinois where it continued to build gasoline-powered locomotives for mine operations. The reputation of the reliability of Whitcomb locomotives spread; so much, in fact, that during World War I the output of the Whitcomb plant was devoted almost entirely to government orders. In 1929, Whitcomb designed and built the largest gasoline-electric locomotive that had been offered to American railroads up to that time. In 1931, the company fell into bankruptcy and was acquired by the Baldwin Locomotive Works of Philadelphia, PA. Baldwin operated its new asset as the Whitcomb Locomotive Works until 1940, when it assumed full ownership and Whitcomb became a division of the parent company. When World War II began in Europe, there was an increased demand for locomotives, both at home and abroad. The manufacturing facility was increased, and by 1942 the factory area had doubled. In February 1952, industrial locomotive production was shifted from Illinois to Baldwin’s Eddystone Works in Pennsylvania.

|

|

|

Three-truck, class B Climax locomotive, Preston Mill Co. , ca. 1926. Special Collections, UW Libraries, C. Kinsey 2920 |

Rogers Locomotives

The Rogers Locomotive Works started its production in 1832, under the name “Rogers, Ketchum and Grosvenor”. It wasn’t originally formed to build locomotives, and didn’t unveil its first locomotive until 1837. The Sandusky was its name, and it was built for the Mad River & Lake Erie Railroad. From this small start, the Rogers grew to build 550 of them by 1854. The original factory was destroyed in a fire and a new factory was built on the corner of Spruce & Market Street. This building is still there. Things continued to go well for Rogers through the Civil war and into the 1880s. The Rogers name had become well known and respected. By the time that Rogers stopped building Locomotives, it had built 6,200 units. But, the difficulty of delivering the engines, along with the Philadelphia builders’ proximity to the Coal and Iron needed, gradually cut into the Paterson locomotive builders. The Rogers Company closed its doors in 1904.

Continue to next section, “Camp Life“