Soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor, public outrage and hysteria turned towards the Japanese (both alien and citizen) living in the United States. The west coast had a long history of anti-Asian agitation culminating in the denial of citizenship (naturalization) to Asians upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1922 (Ozawa v. U.S.) and the 1924 Immigration Act which barred Asian immigration.

War with Japan quickly reawakened feelings of suspicion and fear. Newspaper headlines and columnists began to warn of saboteurs and fifth column activity. Congressmen jumped on the anti-Japanese bandwagon and began spouting warnings of imminent danger from Japanese Americans.

I know the Hawaiian Islands. I know the Pacific coast where these Japanese reside. Even though they may be the third or fourth generation of Japanese, we cannot trust them. I know that those areas are teeming with Japanese spies and fifth columnists. Once a Jap always a Jap. You cannot change him. You cannot make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear….

Do not forget that once a Japanese always a Japanese. I say it is of vital importance that we get rid of every Japanese whether in Hawaii or on the mainland. They violate every sacred promise, every canon of honor and decency. This was evidenced in their diplomacy and in their bombing of Hawaii. These Japs who had been there for generations were making signs, if you please, guiding the Japanese planes to the objects of their iniquity in order that they might destroy our naval vessels, murder our soldiers and sailors, and blow to pieces the helpless women and children of Hawaii.

Damn them! Let us get rid of them now!1

A report commissioned by Congress just after the Pearl Harbor attack largely dismissed these rumors and contended that the vast majority of Japanese Americans were loyal but it did nothing to stop the mounting public hysteria and government and military reactionism. The so-called Munson report found that the Nisei, second-generation American citizens were:

universally estimated from 90 to 98 percent loyal to the United States if the Japanese educated element of the Kibei is excluded. The Nisei are pathetically eager to show this loyalty. They are not Japanese in culture. They are foreigners to Japan. Though American citizens they are not accepted by Americans, largely because they look differently and can be easily recognized. The Japanese American Citizens League should be encouraged, the while an eye is kept open, to see that Tokio does not get its finger in this pie–which it has in a few cases attempted to do. The loyal Nisei hardly knows where to turn. Some gesture of protection or wholehearted acceptance of this group would go a long way to swinging them away from any last romantic hankering after old Japan. They are not oriental or mysterious, they are very American and are of a proud, self-respecting race suffering from a little inferiority complex and a lack of contact with the white boys they went to school with. They are eager for this contact and to work alongside them.2

On February 19, 1942 President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which authorized the military to exclude any person from designated military areas.

I hereby authorize and direct the Secretary of War, and the Military Commanders whom he may from time to time designate, whenever he or any designated Commander deems such action necessary or desirable, to prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded, and with respect to which, the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded, and with respect to which, the right of any person to enter, remaining, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose in his discretion. The Secretary of War is hereby authorized to provide for residents of any such area who are excluded therefrom, such transportation, food, shelter, and other accommodations as may be necessary, in the judgment of the Secretary of War or the said Military Commander, and until other arrangements are made, to accomplish the purpose of this order.3

This order gave the military free reign to designate military areas and to remove any persons considered a danger. On March 2, 1942, Lt. General John L. DeWitt, West Coast commander U.S. Army, issued Public Proclamation No. 1 which designated the entire West coast a restricted military area. The Army issued the first Civilian Exclusion Order for the Japanese on Bainbridge Island on march 24, 1942. Though theoretically Executive Order 9066 could be used to remove German and Italian Americans only the Japanese community was forced to undergo mass evacuation and imprisonment. After all it just wouldn’t be right to imprison Joe DiMaggio’s Italian immigrant parents.

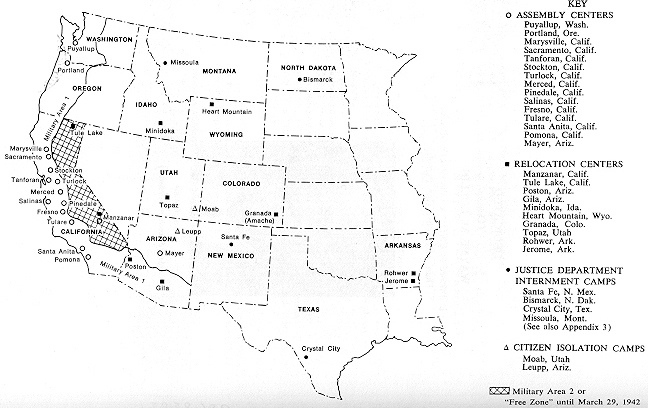

By June 1942 more than 110,000 Japanese (more than 70% of them American citizens) had been forced from their homes into temporary assembly centers. These assembly centers such as Camp Harmony were ramshackle affairs built at racetracks and fairgrounds. From the assembly centers the Japanese were moved to ten concentration camps scattered in the more inhospitable desert regions of the West.

After the war, Japanese Americans returned to the West coast. In 1952 the McCarran-Walter Immigration and Naturalization Act finally allowed Issei naturalization. In 1976, on the thirty-fourth anniversary of Executive Order 9066, President Gerald Ford declared the evacuation a “national mistake.” And in 1988 HR 442 is signed into law by President Ronald Reagan providing for reparations for surviving internees. Beginning in 1990 $20,000 in redress payments were sent to all eligible Japanese Americans.

Notes

Map from Personal justice denied: report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians : report for the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs.. Washington: Supt. of Docs., 1992.

- Congressman Rankin of Mississippi, Congressional Record – House, 77th Congress, 2nd Sess. Vol. 88, pt. 1, pg. 1419. Feb. 18, 1942.

- Munson, Curtis B. “Report on Japanese on the West Coast of the United States,” Hearings, 79th Congress, 1st sess., Joint Committee on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1946.

- Executive Order 9066. February 19, 1942.