Tucked away in small corners of our daily newspapers one finds news items which indicate that the American people are losing their concept of tolerance. Tolerance is a funny word. It implies forbearance of views and opinions differing from one’s own. During wartime it is a difficult yet necessary task to draw a thin line of distinction between one’s own attitude and that of his neighbor. There is a different feeling toward our enemies in this second World War; different from the feeling of Americans during the first War. Then were fighting the German people. Today most of us feel we are fighting the fascist form of government, not the people who make up the aggressor-nations. Yet there are indications that that old feeling of hatred is once more abroad in our nation. Perhaps it is because we are now at war with a people of a different race; an Oriental race….

—University of Washington Daily, February 26, 1942

Although the plight of Japanese American students during the winter and spring of 1942 did not get an extraordinary amount of coverage in the student paper, the University of Washington Daily, much of the coverage was sympathetic. The special war edition published on December 8, 1941 included a lengthy article written by UW student Dick Takeuchi on the reactions of Japanese American students. The article reminds its readers that the students are loyal American citizens simply wearing an “oriental mask.”1

The war edition also included an editorial by fall quarter’s editor, Bill Duncan, warning against mob violence: “Let is [sic] not be said that we were too small of mind to respect the rights of man and the unfortunate Japanese-Americans among us.”2

Soon after the declaration of war, calls for tolerance were made by campus groups and echoed in the Daily. On December 9 the Roger Williams Club, a campus Baptist organization, passed a resolution asking for “sympathy and understanding” for Japanese Americans. The YWCA sent a note to the Daily, saying “sympathy and understanding for Japanese-American students are extremely important at this time. By demonstrating our confidence in them we may give them strength to face this situation.”3

In the first months of 1942 sympathy for the plight of Japanese Americans converged on a petition written by mothers of children at Gatewood Elementary, in West Seattle, demanding that the Seattle School District fire its Japanese American staff.4 Bill Edmundson, winter quarter editor of the Daily, responded in his editorial, “To the Mothers”:5

A delegation of mothers in the Gatewood school district demonstrated vigorously against the employment of 20 Japanese office girls in the Seattle Public schools. The Seattle PTA had previously protested against the same situation on two separate occasions. These mothers are certainly not showing the foresight necessary to bring up an enlightened generation of young Americans. The office girls are all American-born, and have the same rights as other American citizens, regardless of creed or color. One of the reasons we are fighting Hitler is because of his persecution of all peoples not strictly German.

Edmundson is more pointed in an aside in an editorial (dealing with physical education) on February 27: “It’s a strange commentary on modern life when we are expected to go to war to protect womenfolk who do not protect our American ideals on the home front.” Edmundson was not alone in criticizing the Gatewood mothers. Other Daily reporters and students were also critical. Russ Braley, a columnist for the Daily sarcastically suggested that the “patriotic” mothers should vacation in Germany where “they would be appreciated.”6

Reactions to Braley and to Edmundson were mixed. Six letters from students were published in the following days, four in support of Edmundson and Braley (“Thursday’s editorial spoke for many of us who believe that tolerance does not mean weakness and that hysterical hatred does not mean strength or patriotism”) and two in support of the petition (“Do not confuse sensible precautionary defense with intolerance”). Braley responded to one negative letter with caustic sarcasm: 7

Your letter certainly alarmed me. I phoned immediately to see what the Japanese-American girls had done to my little brothers and sisters. But the little tykes were all right, so I settled down to write to you. Look chum, what conceivable good is it going to do to persecute loyal American citizens because their ancestors were born in a country with which we are at war? What do you think they are going to do, burn down the schoolhouse?

Other Safety Valve letters on this page answer well enough your letter so I will stop before I libel somebody.

You spelled my name wrong too. That hurt.

Wider support on campus for the Japanese American clerks materialized after the mass resignation of the twenty-six women. A counter petition signed by more than 1,000 students urged the reinstatement of the clerks. The counter petition declared that the Gatewood mothers’ demands were “undemocratic, intolerant, disrespectful of the rights of American citizens, and detrimental to the best interests of the community.”8

Public Proclamation No. 1, issued on March 2, 1942, designated the entire West Coast as a restricted military area and served as the notification for the removal of all Japanese and Japanese Americans.9 The front-page article in the Daily on March 4 simply read “Campus Japanese Face Evacuation.” The article then slipped slightly into editorializing by noting that the proclamation was “the drastic answer to the frequent public demands for eviction of all Japanese — citizens and aliens alike — from vital defense areas.”10

On March 4 Jack Sheedy, a columnist and reporter for the Daily, lambasted those who supported the evacuation — a group that included the American Legion and some business organizations.

These people you condemn gentlemen are human beings — individual citizens who work and dream as you and I. They are not cattle. And they are not to be herded as cattle. They are humans. Citizens. They speak our tongue. They worship our way of life. They are us. Hurt them and you destroy us. If segregation of our citizenry by racial groups persists, democracy is doomed. How can an utopian democracy thrive tomorrow when inter-racial hate is fostered today?11

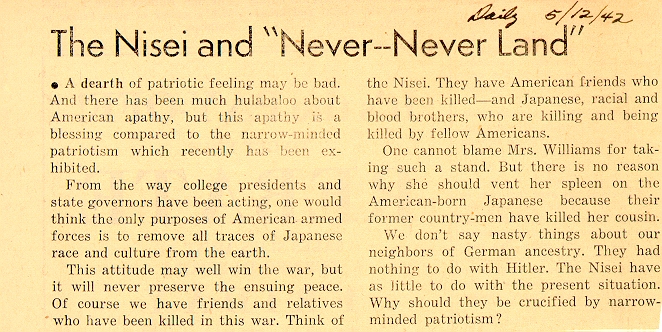

Despite an editorial change in the spring, the Daily‘s stance remained supportive of Japanese American students. In an editorial reacting to the announcement that Japanese American students would not be accepted at Utah State College, Ron Bostwick noted that “[h]ere on the coast where we have constantly associated with the American Japanese we have no thought of prejudice against them. We have played baseball, football, basketball with them; we have worked and studied along with them. We fully realize the younger generation of Japanese are, if anything, more completely American than we are.” The editorial on May 12, “The Nisei and ‘Never-Never’ Land,” lamented the crucifixion of Japanese Americans “by narrow-minded patriotism.”12

The Daily also gave voice to some Japanese Americans through guest editorials and letters to the editor. One guest editorialist struck a tone of patriotic fortitude, noting that “[i]f evacuation is a must in an unimpeded war-effort set-up, I don’t see how anyone with the awareness of what we are fighting for can be against it” and “[a]ll out for defense is the order of the day. Whether their family trees reach back to Benedict Arnold or to the Tokugawas, fifth columnists must be weeded out.” 13 Other editorialists took a less sanguine view of the evacuation, “For the citizens who are so affected, this evacuation announcement has been a severe blow to all that we have been taught to love. It is unprecedented in the history of the United States that even notwithstanding wartime our rights as citizens have been temporarily suspended without the establishment of martial law.”14

Throughout the winter and spring of 1942 the Daily faithfully noted the various committees formed and actions taken concerning the Japanese American students. Coverage slowly petered out once the Nisei were incarcerated. A final poignant letter from a Japanese American student, Yoshiko Uchiyama, written in response to a gift of books and magazines received in December 1942 was partially reprinted in a January 1943 article:15

Not only will the gift be of use to us, but more than that, it will be a constant reminder for us to keep our faith in America — our country which belongs to broad-minded individuals such as those of you who contributed toward the gift. We are ever hoping that the time will come soon when we can all re-enter the America beyond the relocation camps in order that we make our contributions and be considered as an integral part of the American way of living.

All segments of “Interrupted Lives: Japanese American Students at the University of Washington” are copyrighted by the University of Washington Libraries. “Interrupted Lives” may be used online. Segments of “Interrupted Lives” may be downloaded for personal use. The URL may be included in another electronic document.