Twenty years in this chaotic world — living through the world’s greatest depression, and now the second World War, a man made catastrophe beyond human comprehension in scope and horror. There are some who curse their fate for being born to an age such as this — in a way I’m glad to suffer one small portion of the world’s sorrow and horrors — there is so much to be done, so much which must be done — is man, or myself, equal to the task? We will, we must, triumph!!

—Kenji Okuda1

There are many stories that should be told of the University of Washington’s Nisei students: William K. Nakamura, who fought and died in Italy and was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 2000; Gordon Hirabayashi, who resisted the evacuation orders and stood up for civil rights; and the many others who went on with their lives, moving to the camps or to the army or to colleges and jobs. This is but one student’s story, the story of Kenji Okuda, told through his words and letters.

Kenji Okuda was nineteen years old in December of 1941, a second-year student majoring in economics at the University of Washington. His father, Henry Heiji Okuda, was a respected business man in the community and well known among Japanese on the West Coast. Home was a house on Beacon Hill just outside the borders of Nihonmachi (Japan town). Kenji attended Beacon Hill Elementary School and then went on to graduate as salutatorian from Franklin High School. Following a year spent in Japan visiting family, Kenji entered the university.

He began his studies as an engineering student, prompted by his parents’ desire for training that offered the “greatest potential for [economic] security.” Issei parents were concerned, as many parents in the Depression era were, about job security. Medicine and engineering were favored for their marketability both in the United States, and if necessary, in Japan. 2 However Kenji soon abandoned engineering for economics. While at the university he continued his previous involvement in the youth group within the Japanese Congregational Church and was active in the campus YMCA. He later became secretary of the local Y.

Pearl Harbor to Harmony

In 1940 and 1941, like his fellow Japanese American students, and indeed like most Americans, Kenji felt that war with Japan was improbable. The European War, as it was then called, was of greater concern. Students debated the merits of American neutrality and isolationism. To Kenji and his companions, a Pacific War against the Japanese seemed “highly less likely to occur”; an attack by the Japanese “didn’t seem very feasible or likely.”3 The morning of December 7, 1941 changed everything. “And then, Pearl Harbor,” he recalled years later. “I can remember the details of that one. I first heard about it, either somebody called and said, Turn on the radio, about mid morning. It was confirmed on the radio that Japan had attacked.”4 That afternoon, Kenji gathered with others (including Gordon Hirabayashi and Bill Makino) at the YMCA to discuss the attack and possible consequences. “Would things remain normal or would all sorts of disruptions occur.”5 Disruptions began almost immediately.

On the evening of December 7 the FBI began to round up community leaders, and police departments raided homes for contraband such as shortwave radios, hunting rifles and samurai swords. By December 9 more than 1,200 Japanese were in custody nationwide (as well as 865 Germans and 147 Italians).6 The arrests caused panic amongst the Japanese American community. Reverend Daisuke Kitagawa of St. Paul’s Church, outside Seattle, wrote, “every male lived in anticipation of arrest by the FBI, and every household endured each day in fear and trembling.”7

Many of the arrested Japanese were, like Kenji’s father Henry Okuda, Issei community leaders and businessmen with ties to Japan. The FBI came round on the evening of December 7 for Henry Okuda, who was in fact deemed by the FBI to be “the most dangerous Japanese propagandist in the Seattle Area.”8 Years later Okuda recalled the arrest.

That night about 7 or 8 o’clock, we were in the house, I think we’d finished dinner, there was a knock at the front door. The fellow identifies himself as an FBI agent. He wanted to speak to my Dad. My Dad’s comment was, he was getting rather hard of hearing, What, the PI, the Post Intelligencer wants to meet me. No, the FBI. So the fellow came in the front door. Another fellow was with him, the deputy sheriff. Then, at the back door, 15-20 minutes later two more came. Then they asked permission to look through documents. A lot of it was in Japanese. They wanted to take them to get it translated. Then they asked my Dad to go with them. He went down and they were all assembled at the Immigration center downtown. I don’t know how many were in the first round on the night of the 7th. Then they said we hope he can get out shortly. You go down and ask. It turned out that none of them ever got out. Most of them were shipped to Missoula, several months later.9

As in many Japanese families, the restrictions imposed by the Alien Land Acts meant that family property was held in the name of children who were by right of birth American citizens. In the Okuda family Kenji held title to the family home and jointly held bank accounts with his father. With his father’s detention, Kenji took responsibility for dealing with business matters, eventually closing down the family business “for the duration” in early spring of 1942.10

Less traumatic disruptions soon hampered everyday life. Business licenses of Japanese were revoked, their bank accounts were frozen, proof of citizenship was required for travel. Short-wave radios, cameras, guns and other potential weapons were confiscated. Many of these restrictions were later eased for American-born Japanese in the weeks following Pearl Harbor.

Throughout the winter and early spring Kenji continued with his classes and activities with the YMCA. In addition, he served as a student representative on the University Student-Faculty committee dealing with evacuation issues and student relocation to schools outside the restricted military area. The committee conducted a campus survey of “probable alien student evacuees” collecting information on draft status, work experience and finances.11

In February of 1942 Executive Order 9066 was handed down, followed by a number of Public Proclamations by General J.L. DeWitt, Western Commander of the Army. These proclamations reinstituted tighter restrictions on the entire Japanese community, citizen and non-citizen, Nisei and Issei. A stringent curfew was established in March of 1942. Japanese on the West Coast (the entire Pacific Coast was designated a restricted military area) and in inland areas such as Utah, Idaho and Montana, Japanese were required to remain within their homes from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. During the day, all Japanese, according to the proclamation, “shall be only at their place of residence or employment or traveling between those places or within a distance of not more than five miles from their place of residence.”12

The curfew made it difficult for Kenji to attend to his duties as YMCA secretary. He found himself having to leave meetings early in order to be home by 8 p.m. It also hampered his social life, as he ruefully noted in a letter to his friend Norio Higano, “I’ve been behaving very well because of the curfew — but I am planning to stay overnight at the Y. next Friday, and I hope I can enjoy myself.” In the end, his final meeting with YMCA friends was curtailed.13

Before I go very much further, I’d like to say that I left Seattle Thursday, Apr. 30, and Caleb Foote spoke at the Wednesday cabinet dinner. About halfway thru the discussion, we Japanese had to leave — what a feeling. Goodbye — and where were we to go — where would we meet again? Tears came to my eyes as I shook hands with the whole bunch, and what a swell bunch they are!

Kenji Okuda and family, minus Henry Okuda, left home and friends and school and went with the rest of the Seattle Japanese community to a makeshift camp at the Puyallup fair grounds christened Camp Harmony.14

Camp “H”

Here I am, and I’ve been for almost the last two weeks, sitting on my haunches in the “assembly center” — what a name — at Puyallup watching the days roll by. Hell, what a feeling! Cooped in by a fence with armed guards patrolling outside and submachine guns in the watch towers, powerful search lights playing in the area between the barracks and the fence, watched by armed guards the moment we leave to go to another camp — what a mess!15

Kenji arrived at Puyallup in late April as part of an advance staff composed of primarily Japanese American Citizen’s League (JACL) members to prepare the camp for the major influx of Seattle Japanese due in early May.16 The grounds of the Western Washington State Fair in Puyallup were quickly transformed into a camp that by the end of May held more than 7000 Japanese. Stables, grandstands and exhibition barns were retrofitted to house evacuees; more than 165 barracks were constucted that resembled according to one dismayed observer, “rabbit hutches.”17 The camp was divided into four areas, A, B, C, and D. Each area, with the exception of D, had rows of barracks arranged in avenues with latrines and showers located centrally between avenues as shown in the map drawn by Kenji.18

The early days at Puyullap were hectic, as the advance team assigned rooms, transported luggage, furnished mess halls, and organized a governing structure. Okuda later recalled:

I remember the chaos of that early period, we were working 15-20 hours a day, unloading people’s luggage and other materials into the rooms they were assigned. And eating 3 or 4 times a day. Usually we’d eat at 5 and start at 6. Then we’d have another meal before noon and finally another at dinner, then another late at night. Eating Vienna sausages. That’s all they served us for two weeks. I cannot look a Vienna sausage in the face to this day.19

Each area had a “mayor” and an administrative staff based on the military model. Each mayor would report to the central administrator, James Y. Sakamoto, who would then report to the WCCA (Wartime Civilian Control Administration) Manager, J. J. McGovern. Day to day administration lay with the area bureaucrats. Kenji was assigned as Information Officer in Area A. He was responsible for communicating WCCA and military directives to the residents and acting as liaison between residents and outside authorities. In a letter to Norio Higano, Kenji summed up his job, “I have a soft, easy job inside the headquarters now (of Area A) as information manager with a desk, secretary, and what have you.”20

Despite the “easy job,” Kenji raged against the idiosyncratic and dictatorial demands of the Army and WCCA. The hypocrisy of the “evacuation” struck vividly on Memorial Day of 1942, as he wrote his friend Higano, “But how futile and hypocritical this all sounds . . . in concentration camps in a Democracy . . . to be kept herein at the sole discretion of the military . . . and yet to be expected to be willing to do our best to insure the defeat of a nation with which so many of us are connected only by facial and racial characteristics.”21 In a later letter he discussed the travel restrictions faced by Japanese Americans, even those serving in the military: “[T]his regulation is quoted to prevent a Nisei soldier in the Middle West from coming out here to Puyallup, for example, to visit his parents. What irony! A soldier prevented from traveling around freely in the country for which his is fighting because of his racial background. The moment this soldier crosses the Columbia River into Washington, he is unwanted and denied his civil rights.”22

Less than a month after becoming Information Officer, Kenji tendered his resignation as a protest against the establishment of a twice daily roll call of all inmates in the camp. His resignation was not accepted and eventually the roll call dropped to once a day. Kenji’s rebellion also found an outlet in an attempt to hold a no-confidence vote on the JACL established central administration headed by James Sakamoto. According to Army intelligence, pro-Japanese elements, spearheaded by two Seattle attorneys, Thomas Masuda and Kenji Ito, forced the vote by contending that the camp administration was “undemocratic and un-American because its officers were not duly elected by popular vote.”23 A vote was held on June 16 and according to both the Army report and the camp newsletter, an overwhelming majority supported JACL administration.24 Kenji viewed the vote in a different light:

We had a plebiscite recently which is described in the camp paper I’m enclosing — but the manner of holding the election was so undemocratic — a ‘Hitler plebiscite in a Japanese Socialist camp set up by a democracy to be run as a dictatorship’ to quote Esther Schmoe. This election was held at the 9:30pm roll call with no advance notice and the citizens requested to answer immediately to a very ambiguously worded proposition. We have a petition circulating now to have another vote of confidence because of the manner in which the first was held — ought to get at least 1,00 signatures out of 2,704 persons in Area A.25

Kenji’s alliance with the petition movement, coupled with the FBI’s labelling of his father as a “dangerous Japanese propagandist,” made him a trouble-maker in the eyes of the Army. Undoubtedly this was compounded by Kenji’s pacifist stance. He was a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), an interfaith peace organization and he wrote for the Pacific Cable, a publication sponsored by the Seattle area American Friends Service Committee and FOR, which Army intelligence cryptically noted was “receiving considerable attention from this office.”26 Kenji’s pacificism culminated with his registration as a conscientious objector. He wrote, “I registered, finally, as a C.O. with the following “Conscientious Objector to War” written across the face of my registration card. Maybe I did a foolish thing: I don’t think so — but I don’t regret it.”27

On August 3 of 1942, just days before his 20th birthday, Kenji observed in a letter to Higano, “To make or create too much disturbance in the assembly centers is only to arouse the ire of the Army — and then it’ll be a struggle to wrest some power from the W.R.A. to get even with us. And who can buck against the stubborn, dictatorial, authoritative power of the military forces without arousing their ire?”28 Evidently, Kenji did arouse the Army’s ire, for during lunchtime on August 27 of 1942, he was called into the camp manager’s office and told that he and his family “would be leaving on the 4:58 p.m. train” for Merced, California and from there to the WRA concentration camp at Granada, Colorado. He described his reaction: “What a blow! Could I do anything to resist? Was I so powerless as to submit meekly and passively? What could I do? Anything. Sane thought was impossible — a feeling of futility, then a dogged determination to carry thru.” 29 In a later letter written from Granada, he wondered about the reason he got “kicked out” of Puyallup, “Why was I shifted out of Puyallup? The theories are many and divergent, but I doubt very much whether the real truth will ever be uncovered until the end of the war — if ever.”30

Some military records from the time provide the rationale for Kenji’s abrupt removal from Puyallup. According to military reports, Kenji was considered an “agitator” and member of “an alleged subversive group” at the assembly center. These “four subversive Japanese” were not transferred to the Minidoka camp in Idaho with the Puyallup assembly center contingent, but were separated out and moved to different camps which would “have a salutary effect on all concerned.” Furthermore, the abrupt move would throw “them off balance for a few days.” Especially damaging for Kenji’s case, was the “reliable” information that he once stated, “I’ll be damn’d if I’ll serve Uncle Sam.”31

So Kenji and family, still without Henry Okuda, were sent to Merced, and eventually to Granada, a concentration camp in southeastern Colorado, far from their Seattle friends in Minidoka, Idaho.

What a sad parting!!! Those 4 1/2 hours were among the most hectic in my life!!! As I left, my vision was blurred and my eyes stung. So long [illegible], So long Wall — goodbye all — the last of Puyallup Assembly Center and maybe the boys [and] girls in there for the duration!!! I was so numbed I wasn’t fully aware of the significance of the whole thing.32

Granada: A Paradise for the Insect Hunter

This place is full of them — ants, beetles, grass ticks, and a thousand and one other species. A paradise for the insect hunter!!! A couple of nights ago, just before some rain, we had an invasion — they ran into the sides of the building sounding like hailstones striking, they got into the rooms despite the closed door and screened windows, and in one room so covered the bed that the bed covers couldn’t be seen. And the poor bug exterminator, yep we have one employed full time on the payroll, didn’t know what to do with them.33

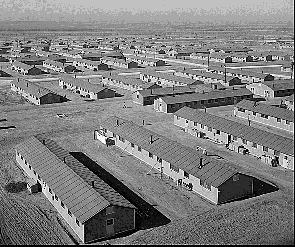

Aside from the wildlife (primarily bugs and snakes) and the weather, (dry, windy and dusty) the Granada Relocation Center resembled Camp Harmony. There were rows upon rows of barracks, interspersed with public buildings — latrines, messhalls, schools, and offices. Kenji viewed the exile to Colorado as a trial, a test of his conscience, a stretching of the heart. In a letter to his friend Norio, written soon after arriving in Granada, he wrote, “I have no reason to regret my actions — if this forced path of trial is a result of my expression of my inner consciousness, I am so sorry that the family was made to undergo the suffering — but I feel that I cannot have taken another path. We cannot live in an enclosed shell entirely apart from society or the smaller unit of the family — my duty now to the family, my conscience, and to God is to make the best — to do what I can — in these circumstances.”34

There were rows upon rows of barracks, interspersed with public buildings — latrines, messhalls, schools, and offices. Kenji viewed the exile to Colorado as a trial, a test of his conscience, a stretching of the heart. In a letter to his friend Norio, written soon after arriving in Granada, he wrote, “I have no reason to regret my actions — if this forced path of trial is a result of my expression of my inner consciousness, I am so sorry that the family was made to undergo the suffering — but I feel that I cannot have taken another path. We cannot live in an enclosed shell entirely apart from society or the smaller unit of the family — my duty now to the family, my conscience, and to God is to make the best — to do what I can — in these circumstances.”34

Religious faith, though always present in Kenji’s life through the YMCA and Fellowship of Reconciliation, takes a much more visible role during his stay in Granada. The meaning of Christian faith, of conscience and spirituality, are threaded throughout his letters during this period. In a letter to a friend written in November of 1942, he writes of Christian faith and his belief that, “true friendship and understanding, can and will exist and survive despite all of the hate, bloodshed, and barbarism which is rampant in the world today. The oftener I experience these moments of grateful prayer, the stronger I feel in my Christian pacifism — love is a binding force which is stronger than any physical violence or unpleasantness. But oh — I need to search and cleanse myself — there is so much of the unchristian, the over materialistic within me!”35

He went on in the letter to explain his belief in the existence of God.

I would argue for the existence of God upon several bases — sensory, rational, and intuitive. The error, if there is an error, in the reasoning that there is no God, is in the manner of thinking. If sensory experiences are the total of reality, then God’s existence cannot be proved – but – sense experiences are not and cannot be the total of reality. If reality is something in existence whether we have a human mind to comprehend it or not — then sense experiences cannot understand the whole of reality — there is no infallibility or all — inclusiveness or finality about sense experiences. Reason is need to bring order out of the chaos of a thousand sense experiences — but beyond reason and sense experience is intuitive knowledge — knowledge which we grasp purely subjectively. It is in this realm that the greatest strength exists for God’s reality — I feel that there is something above & beyond the material world — God. How can I base any conclusions on intuition or faith when they might be mistaken since it is a fallible human machine which caught the thought? If intuitively we feel God, then all things about us fall into a pattern which proves His existence.36

During his stay, he served on the camp church council, an interdenominational Christian group, seeking to establish a Granada Christian Church. Christians, he believed, were marked by “their fundamental actions and ideas” rather than on dogma and creed.37 His liberal view of Christianity, coupled with his strong sense of communion with the Quakers, aligned him with the pacifists in camp, a coalition of Fellowship of Reconciliation members, Seventh Day Adventists, and pacifist-minded non-Japanese camp staffers.

Kenji’s work with the YMCA garnered him occasional respites from the camp to attend meetings and give talks about camp life. In October he attended a YMCA gathering in Topeka, Kansas, and spoke at the State Teacher’s College in Peru, Nebraska. In November, he made a quick trip to Denver to speak to the congregation at the Trinity Methodist Church. These trips to the outside world allowed him to renew his faith and to broaden his “perspective again on the whole life away from the stifling camp atmosphere.”38 Freedom, even “for a day or two, was a thrilling experience,” but he felt a greater need for spiritual freedom.39

Kenji’s time in Granada was one of introspection mingled with frustration — frustration with his efforts to leave the camp for college and a more general frustration with the apathy he found among his peers. The stultifying sameness of camp life drained the initiative of its inmates. Kenji bemoaned the “superficial gaiety” of camp life that revolved around recreational life, a kind of “drug” that produced a “pleasant, stupefying, dulling effect on the mind” and shoved “all serious thought way into the back of the mind.” 40 He returned to this theme in a later talk given at Oberlin College:

Given three meals a day, the chance to work or not as one desires, with plenty of opportunity to meet friends since all live within such a limited area, with dances, socials, and athletic events scheduled throughout the week, life can become extremely pleasant if one does not probe deeply. Each day becomes an end in itself to be lived pleasantly; but such conditions do not lead to an invigorative life, to a sensitive personality which is concerned with more than oneself or one’s physical well-being. It is this effect on the individual personality which, to me, is the most unfortunate aspect of camp life. Ironical it is that many of the intelligent young men and women feel that life in the camps is too easy for them; that they find it more and more difficult to retain the higher values of life.41

These thoughts were expressed in letters to his friends. Those higher values of life, “the spiritual things of life,” could be gleaned out of camp life if only the inmates would open their eyes. Many Nisei were “myopic, short-sighted, and unthinking” unwilling to “stand on their own two feet.”42He worried about the number of “of young people and isseis who can joke and sleep and eat from day to day without thinking of the morrow and calling the existence living!! The future is black — we’re afraid — we’re weak — and so we cling with awful tenacity to the present making a joke out of everything that happens.”43 Spiritual growth could counteract the superficiality and lassitude engendered by camp life, though even Kenji was willing to admit that the “personal discipline” required would be difficult given the “many avenues of distraction.”44

The Japanese could profit from camp life if they could learn “[t]o live, to think, to love — deeper. To appreciate the simple things of life — to appreciate the beauty of nature — to slow down and live for once…”45 The strength gained from adversity and the growth of faith and spirituality could be positive outcomes from the incarceration.

At least one compensation to be derived here — the beauty of the sunsets. The Northwest sunsets were beautiful, but those have such a different type of beauty and solitude and grandeur — truly is it Indian summer. The color of the sky — from the pure white of the gigantic clouds to the orange to the purple — and all of its colorful shades — exhibited in the heavens — how serene, how calm, and yet the people so blissfully ignorant of the breath taking panorama before them go around shouting, yelling, cursing — crying about being deprived of seeing or doing anything worthwhile. Men are so blind — perhaps this evacuation will make those nisei who have the guts and courage to live through it deeper and give them a realization that our materialistic, decadent civilization has not and cannot lay the proper emphasis and perspective — of the values and worth of the much greater worth of the spiritual things of life. But to gain this one lesson would offset tremendously the evil, cancerous effects of the evacuation on the niseis and isseis themselves.46

Not Saboteurs or Spies: The Long Road to Oberlin

When am I going to get out of this hell hole? I certainly don’t know — I wish I did — but it isn’t even certain that we students will be permitted to leave. The picture now is black, but the situation changes from day to day — all the pressure possible is being applied both in Washington and in San Francisco to have the Army okay the schools which will accept the Japanese, but that is the damn bottleneck. It seems that the Army with its smug dictatorial power feels that most of the schools are located near defense plants or important sites and won’t let us out — hell, we aren’t saboteurs or spies!!47

Kenji was to be one of the lucky ones hoping to transfer out of the University of Washington to an eastern college before the evacuation orders came through in April of 1942. In March of 1942, UW President Sieg began to seek places for the UW’s Japanese American students. He sent letters to college presidents of eastern and midwestern schools touting the Nisei as “excellent scholars” and “loyal supporters of academic and defense activities” with the hope that colleges would “open its doors to a few well-qualified American students of Japanese ancestry.”48 The president of Oberlin College, Ernest H. Wilkins, quickly responded by offering admission to Kenji and three other UW students.49 However it would be more than nine months before Kenji reached Oberlin, months of filling out forms, getting permissions, and meeting the labyrinthine, shifting and seemingly arbitrary requirements for student relocation.

In the last month prior to forced relocation of Japanese on the West Coast, a few students with the support of their colleges and universities, and with the help of regional organizations such as the Student Relocation Committees established at the University of Washington and at the University of California, Berkeley, managed to transfer to colleges and universities outside the military restricted zone. During this period of “voluntary evacuation” only some seventy-five West Coast students, out of an estimated population of 2,500 Japanese American students, escaped to colleges outside the restricted zone.50

Those left behind were forced into assembly centers, makeshift camps at fairgrounds and racetracks, to await the move into permanent concentration camps built in isolated areas in the most inhospitable regions of the intermountain west. From these assembly centers and concentration camps, students continued their attempts to relocate to colleges and universities. The Student Relocation Committees and other interested organizations came together to form a national council to aid Japanese American students in their efforts to relocate. The National Japanese American Student Relocation Council (NJASRC), under the sponsorship of the Quaker American Friends Service Committee was established in May of 1942. The War Relocation Authority authorized the NJASRC to set up policies and programs that would “involve the selection and certification of students at assembly or relocation centers” and make “arrangements for the reception of American-citizen Japanese” at new universities and communities. College presidents were assured by the War Relocation Authority that they could be “confident that any student relocated at your university through the efforts of the Council will have undergone a thorough investigation as to his loyalty to the United States.” 51

In her book Face of the Enemy, Heart of a Patriot, Ann Koto Hayaishi explained:

The process of being relocated to a university, college or school from the camps was an arduous one. Students had to complete and send to Washington the required number of copies of Form WRA-130, Form WRA-26, which requested clearance, and a registration form. They had to complete the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council Student Questionnaire as well. Moreover, the students had to ensure that their financial resources were adequate to cover travel costs, college fees and living expenses for a least a semester by providing letters substantiating these claims from banks, notary publics, tenants, trustees, or prospective employers. Students also had to provide evidence of their official acceptance into the college or university. All this material was required in addition to the usual application process of gathering and sending official transcripts, letters of appliation and letters of recommendation. The National Japanese American Student Relocation Council processed much of this correspondence. As part of the relocation process, the NJASRC then had to provide clearance for the college or university by the War and Navy Departments as well as evidence that the public attitude in the college community would not cause any difficulty for the incoming student. It also lined up sponsors who would receive the students and help them adapt to the new community. 52

The NJASRC coordinated this entire process. It gathered all the necessary documents, lobbied universities to accept students, solicited financial aid, sought military clearances and, more importantly, visited camps and provided individual support and encouragement to the students. Mail went to and fro between the camps and the NJASRC offices. Kenji later characterized his correpondence with Tom Bodine, Trudy King and others in the San Francisco office of the NJASRC as “voluminous.”53 The NJASRC estimated that it took 25 letters from the Council to various authorities and colleges to place just one student.54 Like most Japanese American students, Kenji relied on the NJASRC and others in the religious and academic communities for help in traversing the maze of redtape required by the military prior to release. The associate secretary of the national YMCA solicited a community sponsor in Oberlin willing to assume responsibility for Kenji. Robert O’Brien, on leave from the University of Washington and working for the NJASRC, wrote on Kenji’s behalf to the president of Oberlin College to seek a statement of community acceptance from Oberlin’s mayor.55 Kenji recognized that his chances for reloction depended on the work of others, “In the back of my head, I wonder if we’ll be allowed to get out at all, but as long as O’Brien, Mike Masaoka, Joe Conard and the whole bunch of them are still working persistently, there is room for hope.” 56

Kenji’s relocation travails pepper his letters, sometimes with depair, other times with hope : “My chances of getting out are still in the gloomy dark,” he wrote in July of 1942; in August, he stated, “my hopes are reasonably high.” He admitted to Norio Higano that “I seem to change my opinion each and every time I write to you.” 57 The ups and downs of Kenji’s fortunes reflect his frustrations with the arbitrary requirements of relocation, especially those inflicted by the Army, “the most stubborn obstacle” to his release. Security clearance for Oberlin College was the first obstacle. Each university prior to enrolling Japanese American students needed to be cleared by the military. Smaller colleges in out-of-the-way locales were more likely to receive clearance in the early years of the war. Oberlin, according to Kenji’s letter to Higano of August 1942, had been approved by the Army and was awaiting Naval approval. 58

Once Oberlin was opened to Nisei students, Kenji faced an even larger obstacle, security clearance from Army intelligence to leave the camp.

As far as my school plans go, another reversal has occurred & I’ll have to change my view. Tom Bodine gave me a Sp.Del. letter from Frisco today – the Army G.2 (Intelligence) has refused to grant me permission to leave camp. The reason is unknown — I’ll wait until I’m at a WRA Center before pushing my case forward. Tom has two theories as to why I am not being permitted to get out — (1) my C.O. stand. (2) my connection with the Pacific Cable from which I cut out the article by Gordy I was planning to enclose. Personally I think it is the second. If so, influential men will back me up and try to prove the publication not subversive according to Tom. If this gets worse, I’m going to court & apply for a writ of habeas corpus. They can’t deny me privileges which other evacuees can get without a d___ good reason.59

In a later letter he assured Higano that he was continuing to fight the Army for release “with every ounce of strength I can muster.” He went on to say that others who were originally blacklisted were later approved, thus granting G-2, Army intelligence “a little more intelligence than I gave it credit for!” But yet another obstacle was erected — all students were now required to get FBI approval on top of Army and Navy security clearance. This was bound to slow down the process yet again. Though frustrated by yet more redtape, Kenji once again recognized the help he and other Nisei students got from the workers and volunteers of the NJASRC:

Tom [Bodine] writes that if this were a measure pushed in by anti-relocation forces, he could use his energy fighting it, but when it is introduced as just another red tape requirement, the discouragement is overwhelming. And so I have no corner on the griefs and discouragements of the whole effort — in fact mine pale into insignificance when compared with those of the men and women working so vigorously for all of us. Theirs is not work for the profit motive; theirs is the sacrificial effort and therefore more deep-seated both to joy and sorrow, achievement and disappointment.60

Kenji received FBI clearance by January of 1943 but was still awaiting final War Department permission. He had been classified as a “Kibei,” a Japanese American educated in Japan, owing to his post-high-school visit to Japan. Kibei were considered additionally suspicious, and the group was initially not free to leave camp.61 Finally War Department permission was granted, all paperwork processed, all clearances attained, and Kenji Okuda was free to leave the Granada concentration camp:

At long last, and thanks to the efforts of so many on my behalf, I have secured my release. The FBI and War Department have now certified me to be a loyal, upstanding American citizen free to return to the American life and that I am planning to do as soon as I can. Present plans are to leave camp Monday (Jan. 11). (I hope that Mr. Schmoe’s still in Denver or thereabouts), go via Colorado Springs where I plan to visit George Yamada in the CPS Camp, Denver, Lincoln, St. Louis, and Chicago to Oberlin arriving there at the end of the month.62

Ambassadors of Goodwill

The genesis of the stereotype of Japanese Americans as a “model minority” can in some ways be found in the student relocation movement of the 1940s. Nisei students were from the very beginning to be community emissaries, “ambassadors of goodwill.”63 The first students to be relocated were chosen both for their academic abilities and personal qualities. A good candidate would “make a good impression” on the college community and would be mature, self-reliant and adaptable as well as reliable and diligent. A good candidate would be a leader with “evidence of successful Caucasian contacts and contributions to the Japanese community.”64 As such, Kenji Okuda was the ideal candidate.

Oberlin College welcomed its Nisei students. President Ernest H. Wilkins, an early supporter of student relocation, worked closely with the NJASRC, especially with former University of Washington Japanese American student advisor and administrator Robert O’Brien (an Oberlin alum) to offer admission to Nisei students. An editorial in the local paper urged the community to welcome the students and treat them no differently than the 1,800 other students coming to Oberlin College. The editorial emphasized that the students were American citizens, vetted by the military, FBI and local officials, and had “excellent records for scholarship, character and citizenship.” The editorial ends with “we wish for these fellow American citizens an entirely happy and intellectually profitable stay in Oberlin. May their experience here only serve to strengthen their belief, and our belief, in the democratic way of living.” 65

By the time Kenji arrived in January of 1943, there were seventeen Japanese American students enrolled in Oberlin, including fellow UW student Bill Makino, Sammy Oi from UCLA and Soichi Fukai from Berkeley.66 In a letter to Tom Bodine of the NJASRC written shortly after his arrival on campus, Kenji described Oberlin as an “ideal haven” for Japanese American students. He would later characterize his welcome as “very postive — incredible.” Bodine visited Oberlin in May of 1943 and reported that Kenji and the other Nisei students were “rapturously happy.” 67

At Oberlin, the tenor of Kenji’s correspondence noticeably lightened. His letters are filled with the everyday concerns of a male student — classes (German, economics, sociology, political science during his first semester), grades (A’s except for a C in German), and girls (“women, sex & fun — what else can we talk about?”). The contrast between Oberlin and Granada was dramatic. College life is “so damn unreal” compared to the “starkness of camp life,” he wrote. Joy is to be had with leisurely meals, moonlit walks, tossing a baseball with friends, attending a play in Cleveland with a date. 68

Kenji’s was elected student council president mere months after his arrival on campus. He ran on a platform stressing the need for a more vigorous student government with an active social program. He stressed the need to encourage student debate and opinion on “important local and national issues” and the creation of extra-curricular activities that would provide “food for thought and action.” An editorial in the student newspaper, the Oberlin Review, credited his election, not to “an irrational act motivated by reasons of sentiment” nor to a display of “cheap liberalism” but to merit and maleness (the first female Student Council president was elected the following year). According to the paper, Kenji was elected based on “his platform which he capably presented in chapel and in the Review, and also on his chapel address on the relocation problem. 69

As such, Kenji Okuda became in some ways a poster child for the student relocation project, a symbol of the all-American Nisei student. His election was lauded in the concentration camp newspapers, covered by the wire services and even rated mention in Time magazine.70 He provided a modest and light-hearted account to Norio Higano lamenting the need for a tuxedo now that he had been elected:

I haven’t gotten around to purchasing a tux, but I’m afraid that I’ll be needing one soon. It seems that there is a scarcity of men here (for some unknown reason), & so I was nominated for Student Council president. I am now Student Council President of Oberlin College! Greet me with the proper amount of dignity — with the dignity that the prexy of the Associated Students of Oberlin College will receive. I understand the AP & UP were down here to get more news, & so I may have become an “international figure” as the Dean of Men jokingly told me. The news was also broadcast over a newscast & mentioned in the Cleveland Plain Dealer. What a life!!! Only a month & a half here, a part scholarship out of the clear blue sky, & now the Student Council!71

Gordon Hirabayashi, Kenji’s former classmate and YMCA colleague, celebrated the election in a letter to a friend: “From Oberlin comes the news that Kenji Okuda is the new student body prexy. Things have a way of happening in a hurry — it seems Kenji just landed on the campus. He has a way of getting around, does very well as a speaker, has a good booster in Bill Makino, finds very favorable climate among the students there. Ken went through a lot of hell, but he stayed on the beam and I guess that is noticeable to others. That was truly good news to have.”72

All relocated students, Kenji believed, should be emissaries, presenting the “problems of the Japanese and Japanese Americans” to the wider community.73 He carried with him the responsiblity outlined in the Minidoka Irrigator editorial “A Privilege and A Duty.”

Students representing the finest type of nisei youth will make their impression on many a wary community. It is their fortunate privilege to be able to continue their interrupted education. Upon them will rest the obligatory task of reshaping prejudices, of creating a true understanding of things Japanese-American. That is their duty. They carry with them to their colleges and universities a heavy responsibility. For theirs is the task of showing to many a heretofore nisei-less college town that they are regular, saddle-shoed “Joes”, all-American. It is a privilege. It is also a duty.74

Within just a month or so of arrival, Kenji had already spoken at a half dozen local churches and organizations. The NJASRC recognized that Okuda’s eloquence as a speaker on behalf of the Japanese and the student relocation program and recommended him as a speaker to groups and institutions. During his time in Oberlin he traveled around the country, speaking at small schools such as Allegheny College and Wooster (where he participated in sit-ins at restaurants refusing service to Blacks), and at church-related conferences such as the Pilgrim Fellowship in Florida.75

In 1944 Kenji toured the camps and communities speaking about student relocation and the future of Japanese Americans on behalf of the YMCA and the Fellowship of Reconciliation. His speaking schedule was daunting. In a letter to a friend, he outlined his schedule for October 1944: “At the present time I’m resting comfortably on a couch in Prairie du Soc, Wisconsin, some 40 miles north of Madison, the home of the U of W, ready to start off again this afternoon to speak at a little town some 15 miles away and then off tonight for Chicago, St. Louis, Tulsa, Oklahoma, around to the Nashville F.O.R. conference and then to camp, Denver, Heart Mountain, and finally back to college on Nov. 1 or thereabouts.” 76

Aftermath

Kenji Okuda left Oberlin in early 1945 and returned to Seattle soon after the military restrictions were lifted on the West Coast. He found work initially as a dispatcher for the Port of Seattle. He continued to speak on issues dealing with race relations, such as a YWCA –sponsored panel discussion on the “prospects of overcoming racial problems in establishing world unity in June 1945.77

However Kenji did not stay long in Seattle. The city seemed too provincial after his experiences in Oberlin and other parts of the country. Seattle, he wrote to a friend, hasn’t “changed much in the last three years” and is a “rather pleasant, but nevertheless confining place.” He went on to note that “race tension has increased markedly, the city has grown a little dirtier, and restrictions are still too damn tough.” Graduate school beckoned, “the sooner I head for graduate school, the happier I’m going to be. College is, no matter what one says, a relatively pleasant escape from life.” 78

So what did the future hold for Kenji Okuda after leaving Oberlin? In a recent interview, he briefly summed up his career:

I left Oberlin College in January, 1945 short a few credits of graduation and returned to Seattle to experience being one of the first Japanese Americans to do so after the evacuation order was lifted. I remember warmly the reception I received at International House and being given the opporunity to spend some time there as a resident. Subsequently I went to Harvard, got my MA, and then taught at Franklin and Marshall College, the University of Puerto Rico and Bard College before settling down at Washington State University. While at WSU I completed work on my Ph.D.

In 1960, I went to Lahore, Pakistan to teach at Hailey College for one year as part of a WSU project funded by USAID. I finally left south Asia after working in Karachi, Pakistan and Nepal and joined Simon Fraser University in 1966, a year after it opened. During my time at SFU, I spent several years in Africa working with governments in support of their development efforts.79

Decades later, Kenji Okuda would look back on the turbulent years of 1941 and 42 and see the benefits to the Japanese American community rather than the costs:80

While the evacuation had difficult ramifications emotionally, I don’t particularly feel any regrets. For those of Japanese descent, the evacuation opened our eyes and our horizons. We were able to leave the West Coast and the cocoon-like existence we had been in. I met people from all over the country, and during the war and immediate post-war periods I could travel to any major city and find someone I knew.

All segments of “Interrupted Lives: Japanese American Students at the University of Washington” are copyrighted by the University of Washington Libraries. “Interrupted Lives” may be used online. Segments of “Interrupted Lives” may be downloaded for personal use. The URL may be included in another electronic document.