Our Japanese students deserve friendliness at this difficult time. There is little doubt but that they will all be taken away shortly. Even though they may be permitted to stay until the end of the quarter, many of them have the serious problem of getting their houses in order, and so will be inclined to drop out of school before the end of the quarter.

—UW President Lee Paul Sieg1

President Sieg wrote these words to UW deans just days after the entire West Coast (all of California and the western halves of Oregon and Washington) was designated a restricted military area under General John L. DeWitt’s Public Proclamation No. 1.2 The proclamation made forced evacuation of the Japanese Americans inevitable. With that inevitability the University of Washington shifted gears, from boosting morale by helping Nisei students cope with restrictions to adopting a leadership role in transferring students to university and colleges outside the West Coast.

Because of the exigencies of war, the Army has given advance notice of the evacuation from this area of both native and American born Japanese. Between three and four hundred members of the latter group are students who have been enrolled in the University of Washington this year.

We have known these students as excellent scholars and young people who have contributed their leadership to our classroom work and constructive campus activities. As a group, their scholarship is well above the University average. As citizens of the University community, they have been loyal supporters of academic and defense activities.

Some of these students will wish to continue their education in institutions away from the Pacific Coast area. We are interested in seeing, in so far as it is possible, that the students of this group be given every opportunity to do so.

This letter is in the nature of an exploratory note to inquire whether your institution would be in a position to open its doors to a few well-qualified American students of Japanese ancestry.

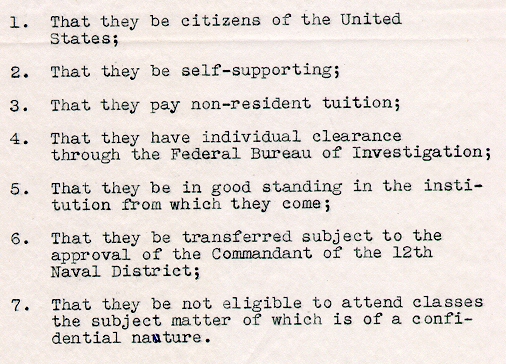

Responses to Sieg’s letter varied, according to a Japanese Evacuation Report written by Tom Bodine of the American Friends Service Committee (this Quaker group was also working to relocate students). By March 26 Sieg had received twelve replies (out of approximately thirty letters sent) with ten universities agreeing to take some students.5 A memo from the office of Student Affairs published a list of those universities and colleges willing to take Nisei students, along with those who could not “accept students at this time.”6 Some universities outlined a number of restrictions, for example the University of Colorado sent this list of requirements: 7

This personal appeal from Sieg to other university presidents was essential in the early move to relocate students prior to the establishment of any official process and organization. At this point, during the spring of 1942, the relocation of Japanese American students depended entirely on the initiative and good will of college administrators. The case of Oberlin College provides a good illustratration.

Oberlin President Ernest H. Wilkens responded to Sieg’s letter with an invitation to four UW students (Kenji Okuda, Norio Higano, Richard Imai, and Koichi Hayashi) recommended by Harry Yamaguchi, a sophmore at Oberlin. Robert O’Brien quickly responded on Sieg’s behalf, thanking Wilkens for his “generosity and cooperation in helping us find a place for some of our best students.” Other letters followed concerning possible substitutions for the students and the issue of community acceptance. By the fall of 1942, another UW student, Bill Makino, was entering Oberlin; Kenji Okuda joined him that winter.8 One student wrote O’Brien during the summer of 1942:9

There are no exceptions or restrictions. The war hasn’t affected their policy a bit. . . . [T]here are eleven of us Nisei students at Oberlin, and my only regret is that some more of the Nisei students are not here to benefit by Oberlin democracy. It is indeed a pleasure and an inspiration to attend such a school where you are treated on an equal basis with everyone else.

The support of the Nisei students extended beyond the college campus to the community at large. An editorial in the Oberlin News-Tribunepraised the students as “fellow Oberlinites” who though of Japanese ancestry “have in every way behaved according to the best traditions of the land of their birth and rearing and citizenship.”10 Oberlin’s enrollment of Japanese American students quickly jumped from two in 1941 to twenty in 1943.11

The University of Washington also established a Student Relocation Committee, chaired by Robert O’Brien. The committee’s mandate was: “1) to gather data on the Nisei in the Pacific Northwest; (2) to collect character references for the students; (3) to help relocate Nisei in other colleges after their evacuation.”12 The Student Relocation Committee later merged with other organizations to form the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council (NJASRC) in May of 1942, which operated with the blessing of the War Relocation Authority (WRA). Robert O’Brien later took an official war leave from the University of Washington to become the director of the NJASRC.13

Other faculty members joined in the effort to support the Nisei students. A letter soliciting scholarship funds made the faculty rounds in early April of 1942. The letter began with George Yamaguchi’s somber note, seen tacked on a study room door: “Working on the final term paper of my career. Please do not disturb. Let’s make it a masterpiece.” Faculty were urged to donate funds so that George and other students could continue their education elsewhere. Continuation of their education and training would “enable them to aid the war effort of the United States” and make “it possible for them to serve our country to the maximum of their ability.”14

The process for transferring a student was rigorous. By July of 1942, the Department of War and War Relocation Authority (WRA) required dossiers for each student (containing references and transcripts) and mandated eight additional steps, including security clearances from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Office of Naval Intelligence, Army intelligence and the War Department.15 In addition, colleges and universities needed to be cleared by the Army and Navy before Nisei students could enroll. During the first part of the war, smaller colleges were more likely to receive clearance rather than the larger state universities, which were more heavily involved in wartime research or military training activities. As of September of 1942, 111 of the 156 colleges that had accepted Japanese American students received clearance from both branches of the military.16

Even after a student had been accepted to a college, obstacles remained. In April of 1942, Kenzo Kuroda, a UW student on his way to the University of Minnesota was detained in Nampa, Idaho. He sent an urgent telegraph to the UW’s Dean of Men. Dean Newhouse in turn asked Pastor Leroy Walker, of the First Methodist Church in Nampa, to intervene on Kuroda’s behalf. Newhouse ended his message: “Thank you for a big favor to a deserving American citizen.” Kuroda was released and allowed to continue his train journey to St. Paul. Walker congratulated Newhouse on his tenacity: “We wish to commend your spirit and your faithfulness in following up your students and in trying to see that they get a ‘square deal.'”17

Minnesota was detained in Nampa, Idaho. He sent an urgent telegraph to the UW’s Dean of Men. Dean Newhouse in turn asked Pastor Leroy Walker, of the First Methodist Church in Nampa, to intervene on Kuroda’s behalf. Newhouse ended his message: “Thank you for a big favor to a deserving American citizen.” Kuroda was released and allowed to continue his train journey to St. Paul. Walker congratulated Newhouse on his tenacity: “We wish to commend your spirit and your faithfulness in following up your students and in trying to see that they get a ‘square deal.'”17

Idaho became the center of another controversy regarding relocated Japanese American students from the University of Washington. Six Nisei were accepted to the University of Idaho in Moscow in the spring of 1942. They arrived to face vigilantes demanding their expulsion from the town and the university. Two female students were placed in protective custody in the town jail. One student’s letter describing the incident was later published in the Pacific Citizen, the newspaper of the Japanese American Citizens League.18

We had our lunch in the face of the deputy sheriff who is called the Bull Moose. He sure hates us. The jailer was talking to someone over the telephone, and said that he is afraid that a mob will come to lynch us tonight.

They don’t have curfew here, but I’m not free in jail, that’s sure, and I’m getting a terrific cold since the place is freezing. Let’s hope Mr. D–– gets his brother in Chicago to take me. Mrs. B–– will mail this letter.

I’ll write you another letter as to how it will turn out, and in case you don’t hear from me, you’ll know what has happened.

Please write. I’m scared.

The governor of Idaho, Chase A. Clark, further aggravated the situation by stating that, “no out-of-state Nisei would be allowed to enroll in any of the state’s institutions of high learning.” The students later enrolled at Washington State College in Pullman, directly across the border from Idaho.19

As the May 1 deadline for the removal of all Japanese from the Seattle area loomed, the university produced a number of memos outlining withdrawal and transfer procedures.20 By the middle of May, O’Brien reported in the Daily that “fifty-eight Nisei students were placed in 15 different colleges in 12 states.”21 The university, at President Sieg’s insistence, also eased graduation requirements for seniors faced with relocation. Years later, O’Brien recollected:

Many Nisei were about to graduate but they were in the last quarter, not allowed to attend the University because they were sent to Puyallup and other relocation centers. President Sieg felt that the better service would be done if they were given degrees. Some of these deans — I try not to remember who they are — felt that this was outrageous, that the degree could not be given to a person who had had eleven twelfths of their education. But President Sieg knew what he thought was right, and the University awarded students who came within – completed 11 quarters, and one of the most encouraging things for those behind barbed wire was when President Sieg and some of his deans went to the relocation centers and gave these young people their degrees. I may be prejudiced for the University of Washington because it’s my alma mater but I don’t think there was anything like this going on other places. We also carried our extension courses to some of the relocation centers as a service to people whose parents were still taxpayers even though they weren’t living with us.22

O’Brien continued his work with the Student Relocation committee (later to become the Northwest Student Relocation Council) throughout the summer by providing updates to UW students at Camp Harmony, the Puyallup assembly center where most of Seattle’s Japanese were detained, and Minidoka, the “permanent” concentration camp in Idaho.23 Student questionnaires were distributed to elicit information from students wishing to relocate. Students were asked about citizenship status, religious preferences and life goals.24

By the end of the war more than 3,000 Japanese American students had been placed in more than 500 colleges and universities in forty-six states. The War Relocation Authority would laud the student relocation effort as contributing to increasing opportunities for the Nisei across the country. A 1945 journal article stated that:

From the point of view of the students, this adjustment program has enabled a number of the most able and ambitious young people to break away from the isolation of the relocation centers and to prepare themselves for making contributions to the life of the country of their birth and loyalty. To many of them, embittered by the apparent disregard of their citizenship, it was a welcome gesture of friendship and recognition of their identity with other young Americans. To many of them also, it will bring an opportunity for a career in work that was closed to them in their former homes. To some of them, it will mean establishing a home for themselves and their families in a portion of the country where lack of concentration removes them from the category of a “minority problem,” and where they are accepted more generally on individual merit. This acceptance is one of the goals of the WRA program.25

All segments of “Interrupted Lives: Japanese American Students at the University of Washington” are copyrighted by the University of Washington Libraries. “Interrupted Lives” may be used online. Segments of “Interrupted Lives” may be downloaded for personal use. The URL may be included in another electronic document.