This exhibit highlights primary sources on two famous strikes in Seattle’s history. Included are facsimiles of contemporary news accounts and headlines, ephemera, memoranda, meeting minutes, and photographs. Most items are from holdings of the University of Washington Libraries’ Manuscripts, Special Collections, University Archives. A short visual version of the larger exhibit, which was displayed in the Libraries from March 4 to April 12, 1999 and the Seattle Labor Temple in July and August 1999, is presented here.

1919 General Strike

Chronology of the Seattle General Strike

On January 21, 1919 months after the end of World War I, the Metal Trades Council in Seattle’s shipyards declared a strike over a wage dispute. The Seattle Central Labor Council voted two days later to join the metal workers in a sympathetic general strike of the entire city, involving over 130 unions and 60,000 workers. For four days in early February 1919, the Seattle labor establishment closed down the city and captured nation-wide attention in the first city-wide general strike in U. S. history. Politicians and newspapers in the Pacific Northwest and throughout the country interpreted the action as the beginning of a Bolshevik-style revolution.

Journalist Anna Louise Strong’s editorial for the labor-owned daily, the Seattle Union Record, unnerved citizens with its Marxist sentiments. It became the celebrated manifesto of the General Strike’s radical mystique and launched Strong on her travel and writing career in the Soviet Union and in China.

Seattle’s labor leaders did advocate a radical-progressive agenda and many rank-and-file workers espoused some form of syndicalism — the idea that people should participate democratically in decisions about work and production. But the General Strike of 1919 was largely a defensive action Workers and their unions struck to protect the economic, organizational, and political gains made during World War I. Business, particularly the shipyard owners, sought to curb labor’s power, believing that it was too strong and that the city should “be run for the benefit of all the people, not a particular class.”

Federal shipbuilding official Charles Piez resisted attempts to compromise on shipyard workers’ demands. His telegram to employers (Metal Trades Association) was misdelivered to the Metal Trades Council, outraging workers.

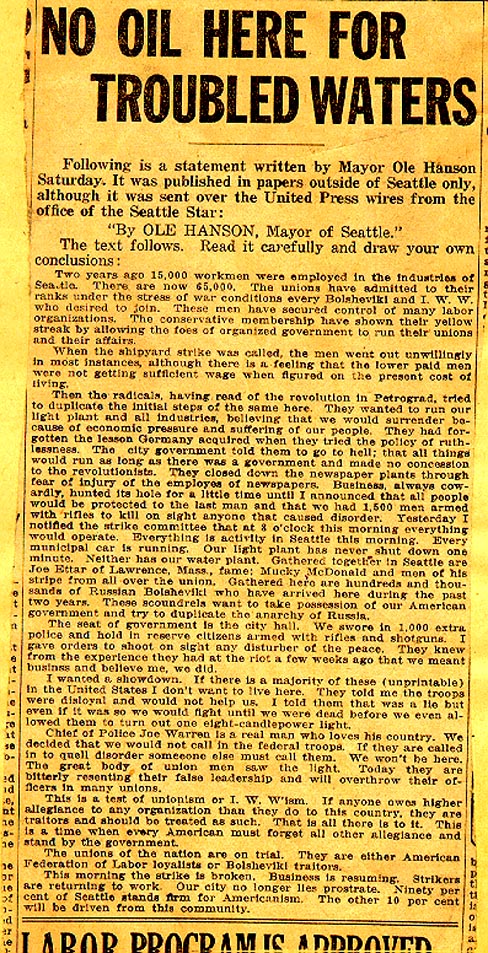

Portion of statement issued by Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson probably on Saturday, February 8th, 1919. It was published in papers outside of Seattle only, although it was sent over the United Press wires from the office of the Seattle Star.

“…The seat of government is the city hall. We swore in 1,000 extra police and hold in reserve citizens armed with rifles and shotguns. I gave orders to shoot on sight any disturbance of the peace. They knew from experience they had at a riot a few weeks ago that we meant business and believe me, we did.

I wanted a showdown. If there is a majority of these (unprintable) in the United States I don’t want to live here. They told me the troops were disloyal and would not help us. I told them that was a lie but even if it was so we would fight until we were dead before we even allowed them to turn out one eight-candlepower light…”

The legacy of the Seattle General Strike is mixed. The unions demonstrated that they could not only halt production, but also maintain essential city services, such as health care, feeding the hungry, and caring for children and the elderly (the unions served between 20,000 and 30,000 meals a day in their kitchens). And Seattle workers were not alone; 1919 was a year of large-scale labor unrest. More than four million workers — one out of every five — participated in a strike that year. But in Seattle and around the country, business and civic leaders responded to this show of force with a “red scare” that turned public opinion against the demands of workers and justified the open violent repression of strikes.

1934 Waterfront Strike

After decades of organizing, reorganizing and failed strikes, longshore workers in ports from Seattle to San Diego hit the bricks once again on May 9, 1934. Longshoremen had joined the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) under President Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Act, which gave workers the right to join unions of their choice and to bargain collectively. When shipping and stevedoring employers refused to bargain with the ILA the men struck.

The longshoremen asked the Seattle Central Labor Council for a work stoppage by all union labor in the city. But Dave Beck and the Teamsters blocked a Labor Council vote at the end of May, and talk of a general strike died out. Together with Ryan, local Teamster boss Beck had urged Seattle strikers to secure their own deal with employers, but Puget Sound longshoremen maintained coast-wide solidarity.

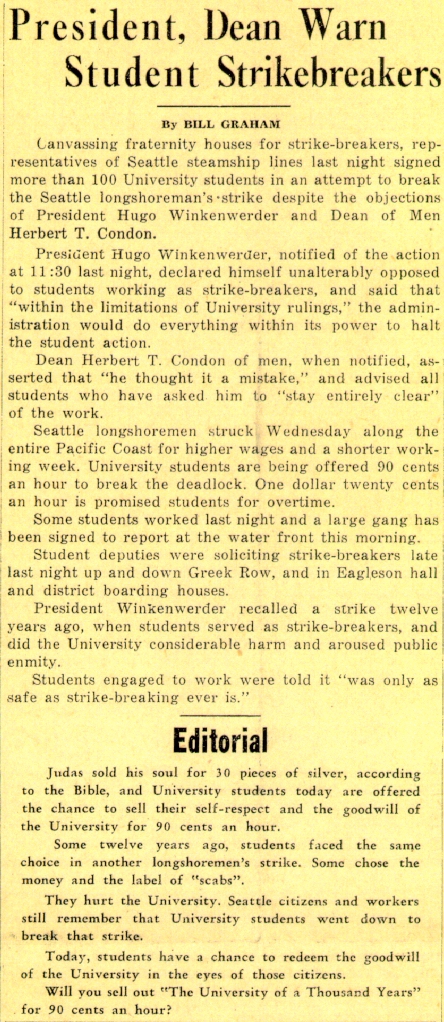

Employers transported strikebreakers by boat to their jobs in order to evade the picket lines that sealed off entry to the docks. At the University of

In this explosive atmosphere, the Waterfront Employers agreed to recognize the ILA on July 21 and arbitrate all outstanding issues with maritime unions if the longshoremen would accept arbitration. A coast-wide vote was taken among the ILA members on the question. Longshoremen in 17 coast ports voted 6,378 to 1,471 in favor of arbitration.

Longshoremen returned to work on July 31. The strikers voted to submit the strike issues to arbitration, with Everett being the

This was a major victory. The Tacoma local was exempted from this provision because its hall remained under full union control, setting the standard for the rest of the industry. The award also granted wage increases to 95 cents an hour straight time and $1.50 for overtime, a shorter week of thirty hours, and a six-hour day.

The union had survived an 83-day strike after lying dormant for 14 years. In the words of a participant: “We had a new sense of our worth, of our power as workers. We instituted many of our own rules: strikebreakers were dismissed; if the load was too heavy it was sent back. The shopowners were only too eager to have their cargo moving again, so they went along with us.”